If Only: Presidential Candidates Could Only Campaign In Person

We've had political television ads for 72 years. We've had political newspaper ads for 196 years. We've had enough.

What if presidential campaigns were stripped down to their bare bones? Imagine a political landscape where candidates were only allowed to campaign in person, with rallies, town halls, and door-to-door visits as their only means of reaching voters. No TV ads, no social media posts, no well-crafted newspaper advertisements. In this “if only” scenario, candidates would have to rely solely on their presence, personality, memory, intelligence, gut reactions, authentic beliefs, and spoken words. Sounds almost unthinkable in our modern, media-saturated world, doesn’t it?

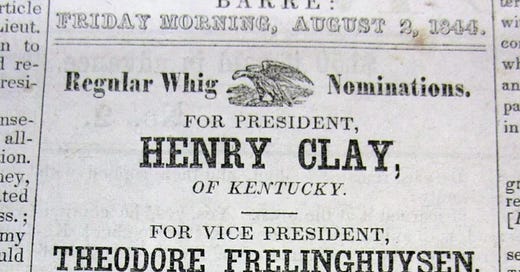

But this idea isn't entirely detached from reality. Campaigns were once much closer to this model. The use of advertisements in U.S. presidential campaigns began humbly, with newspaper ads gradually becoming more prominent throughout the 19th century. One of the earliest documented instances of this strategy occurred in 1844, when the Whig Party placed ads in newspapers like the Barre Patriot (Vermont) to support Henry Clay's candidacy¹. Even earlier, Andrew Jackson’s 1828 campaign employed similar tactics, using newspaper ads to push back against rival John Quincy Adams². And - sadly - even during this early era of political campaigning via media, there was often a fine line between editorial content and advertising - newspapers sometimes even functioned as overt extensions of political parties³.

It wasn’t until the 1950s that political advertising took its biggest leap forward with the advent of television. In 1952, Dwight D. Eisenhower recorded the first-ever TV spots for a presidential campaign, bringing a new era of political communication into American living rooms⁴. The "Eisenhower Answers America" spots took a question-and-answer format with everyday citizens - an unbelievably straightforward and almost wholesome approach compared to the type of campaign ads we’re used to seeing on television and social media in the 21st century. Since then, presidential candidates have poured billions into creating and distributing polished, focus-group-tested ads designed to capture voters’ hearts and minds—or at least their attention.

In today’s campaign world, billions of dollars are spent not just on traditional ads but also on digital marketing, micro-targeting, and social media campaigns. While these tactics offer broader reach, they often prioritize soundbites over substance, and spin over sincerity. This creates an ecosystem ripe for disinformation, polarization, headline-mongering, undue influence by corporations and billionaires, and a general sense of detachment from the candidates as real people.

So, what if we rolled things back? What if the only campaigning allowed was in person? First and foremost, it could foster a more genuine connection between candidates and voters. Imagine a campaign where candidates are forced to slow down, visit different communities, and actually engage in conversation. This approach would require candidates to be more transparent, more adaptive, and less reliant on the messaging of well-paid consultants. With no TV cameras or ad scripts to hide behind, candidates would need to be knowledgeable about policy, quick on their feet, and, perhaps most importantly, genuine. And maybe - just maybe - all of the billions of dollars spent on political ads could go to something more useful to American citizens. Here in Vermont, we have a robust political town hall culture, including our famous Town Meeting Day - a form of direct democracy that exists nowhere in the world outside of New England. So obviously, this Vermonter is intrigued by the possibility of presidential campaigns being conducted with the same vigor, authenticity, and in-person no-nonsense approach we enjoy with local politics here in the Green Mountain State.

But this idealized scenario isn't without its pitfalls, of course. A return to in-person-only campaigning could inadvertently favor candidates with the most time, health, or financial resources (though the latter is certainly already true nowadays, sadly). It would be much harder for working-class candidates or those with limited mobility to participate on equal footing (again, already true, very unfortunately). Additionally, it could limit voter access to campaigning, especially in rural areas, where candidates might not reach every corner of the map (though, for the most part, we’re already largely ignored anyway…unless there’s a unique controversy about a town in the election cycle, or a candidate needs a wholesome rural-America photo op).

Even so, this thought experiment highlights some very real issues within our current system. The overwhelming flood of information—the overwhelming majority of it crafted by marketing teams rather than the candidates themselves—creates distance rather than closeness, and favors polish and clickbait over substance and depth. An emphasis on personal interaction could, in theory, restore some sense of authenticity to the democratic process.

Is this scenario practical? Probably not. But it's worth pondering whether a shift toward more face-to-face engagement, even on a smaller scale, could offer a healthier political dialogue at the national level.

After all, sometimes imagining the impossible helps us understand what's wrong with the actual.

Thank you for reading this edition of “If Only”, one of the six distinct columns that make up To Be a Good Vermonter. If you’re new to TBAGV, please check out this post, this post, and the About Page for some grounding…and of course, please support this work by subscribing (for free) and sharing with friends and fellow readers.

Warmly,

Jack

Footnotes

Virtual Vermont - Whig Party Ad Supporting Henry Clay (1844)

Wisconsin Historical Society - 1952 Presidential Campaign Television Commercials

Other Resources (Included Above)

One example of “Eisenhower Answers America” from the Congressional Archives Carl Albert Center (on YouTube).

An explanation of Town Meeting Day, a quintessential Vermont tradition and a part of our cultural fabric.

For a more personal, narrative, captivating look (or, erm, listen) into Town Meeting Day, please enjoy this incredible episode of Rumble Strip, a Vermont-centric podcast by the inimitable, Peabody-Award-winning journalist Erica Heilman.

“The anatomy of a smear: How a lie about Haitian immigrants went viral” - a Vox article about the conspiracy that shook the small town of Springfield, Ohio.