An Ideal State: Five Historic Utopian Visions to Dream About (or Scoff At)

The good, the imperfect, and some common critical takes on five historic utopian models from philosophy and literature.

What we consider utopian - an ideal state - depends on the values and beliefs we hold…and from among those, which we most prioritize. We may not like to admit it but it’s not uncommon for one or more of our idealizations to be in conflict with another. Since we can’t have our cake and eat it, too, choices must be made.

Here are five utopian philosophies to chew on this weekend. As you read, consider what values and beliefs the creators of these philosophies may have prioritized…and imagine what your own utopia might look like based on your prioritized values and beliefs.

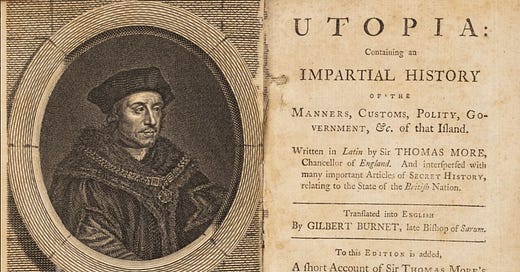

1. The Utopian Island by Thomas More

In his book Utopia, Thomas More describes an imaginary island with a perfect socio-political system. It is a community based on equality, rational governance, and shared resources. More’s utopian vision questions the flaws of his contemporary society—like corruption and greed—by contrasting them with a place where property is communal, laws are simple, and citizens live in harmony. More’s work reflects both a critique of real-world problems and a speculative model for a more just and equal society.

Critique: Detractors argue that More’s Utopia is - gasp! - unrealistic and overly idealistic, in part because it assumes that communal living can effectively eliminate human vices such as ambition and greed. Critics also point out that More's Utopia requires a level of homogeneity that suppresses individual diversity and freedom.

2. Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Noble Savage

Rousseau envisions an ideal society where humans return to a more natural and simple state, free from the corrupting influences of civilization. He argues that people are inherently good but are corrupted by social institutions like property and government. Rousseau’s utopia involves a community that fosters moral development through the general will—a collective interest aimed at the common good. In this society, freedom is not about individual autonomy but about participation in the collective decision-making process, allowing individuals to be truly free through communal governance.

Critique: Critics of Rousseau contend that his vision romanticizes a "noble savage" ideal that ignores the complexities of human nature and fetishizes indigenous peoples. Additionally, the emphasis on the general will can potentially lead to authoritarianism if collective decisions suppress individual rights and freedoms.

3. Plato’s Ideal Republic

Plato’s vision of an ideal world is centered around a structured society led by philosopher-kings, individuals guided by wisdom and rationality. In this ideal state, the community prioritizes collective well-being over individual interests. Justice is achieved when everyone performs their roles in harmony with their natural aptitudes. For Plato, a perfect world is governed by reason, where societal organization reflects the hierarchy of knowledge and virtue.

Critique: Critics argue that Plato’s Republic is inherently elitist and authoritarian, as it relies on a rigid caste system that limits personal freedom and mobility, potentially stifling individual aspirations in favor of collective order.

4. Aristotle’s Pursuit of the Good Life

Aristotle’s utopia emphasizes eudaimonia, or human flourishing, as the ultimate goal. Unlike Plato’s abstract model, Aristotle's ideal world focuses on practical ethics, where personal virtue and communal well-being align. An ideal society, according to Aristotle, is one that encourages citizens to develop virtues such as courage, temperance, and wisdom, thereby enabling a balanced and fulfilling life. The focus is on the pursuit of moral virtues, achieved through good governance and the cultivation of habits that lead to ethical living.

Critique: Some critics highlight that Aristotle’s vision lacks specific mechanisms for ensuring social equality, as it assumes that individuals will have equal opportunities to develop virtues—an assumption that may not hold in real-world societies shaped by disparities in wealth, power, and education.

5. John Stuart Mill’s Harm Principle

John Stuart Mill’s ideal world is one that maximizes individual liberty while minimizing harm to others. For Mill, a utopian society is one where personal freedom is respected, provided it does not infringe on the well-being of others. He champions utilitarianism—the idea that actions are right if they promote the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. Mill’s vision emphasizes the balance between individual rights and societal welfare, proposing that a harmonious society is possible when liberty is aligned with ethical responsibility.

Critique: Critics of Mill’s approach argue that utilitarianism can justify actions that are harmful to minorities if they serve the majority’s happiness, making it a potential tool for perpetuating inequality. Additionally, defining "harm" can be subjective, leading to debates over what limits should be placed on individual freedom.

As you chew on these flawed but ardent utopian philosophies this weekend, please consider: what three values or beliefs do you hold that you’d most highly prioritize if you were given the chance to establish your own utopian project?

Happy Thursday and happy weekend, all.

Warmly,

Jack